A series of reflections on my most recent trip to Burma.

By Jan-Philipp Sendker

Yangon, in the fall of 2013

When I travel in Burma, I rarely have a schedule or a firm itinerary. Instead, I try to follow my intuition. On this trip I wanted to go down south to Moulmein (Mawlamyaing), but I had no clue why or what I wanted to do there. I did not know what to expect, I did not know anybody in town.

I only knew that it is the fourth largest city in the country with more than one million inhabitants, that it is very hot and humid, and that the British writer George Orwell was once stationed there or nearby. And I liked the name. Moulmein sounded very exotic and romantic to me.

There were three ways to get there: I could rent a car, take a bus, or the train. A rented car and a driver was by far the fastest and most expensive. The bus the cheapest, and would take 8 to 10 hours. The train did not make any sense: it was more expensive than the bus, but less comfortable and slower. The trip would take 12 to 14 hours.

I love train rides in Burma. They are a reminder of an age when time did not matter so much. When efficiency was not a paramount concern. When getting from A to Z was a real effort.

A friend of mine and I booked two seats in the Upper Class. It is not much different from the Ordinary Class, except for the reclining seats that did not recline and the fans that did not work. We kept the windows open and the train drove slowly through a lush and green countryside. Enough time to watch water buffalos next to the tracks, kids playing in ponds, women doing laundry in rivers, people preparing their food.

Once in a while it got so bumpy that we were thrown out of our seats and had to hold tight. If it had been an airplane rather than a train, I would have had a heart attack.

Once in a while it got so bumpy that we were thrown out of our seats and had to hold tight. If it had been an airplane rather than a train, I would have had a heart attack.

When we arrived, it was raining heavily in Moulemein. It was still raining the next day. And the day after. (Only later did I learn that it is one of the rainiest places in all of Burma). At the hotel we asked if there was anything to see in town, and the friendly young woman looked at us, puzzled. “Nothing in particular,” she said.

I started to wonder if I had made a mistake. Maybe there was no hidden reason why I felt the urge to go to this rainy place. And then I met Sister Martha.

I started to wonder if I had made a mistake. Maybe there was no hidden reason why I felt the urge to go to this rainy place. And then I met Sister Martha.

Before we left Yangon, a friend of mine had given me her name and phone number. If I did not have anything else to do, he told me, I should contact her. She was an impressive woman running an orphanage.

I called her, and she invited us to her village, about an hour south of the city.

We hired a car that drove us to the little town, and a few minutes after we had met her, I knew why I was here.

Sister Martha is one of the most impressive people I have ever met: a Catholic nun in her early sixties, gentle, very soft spoken but very determined.

There are around twenty kids in her orphanage and they are all HIV positive. Their parents died of AIDS or related illnesses.

“When I started out more than ten years ago, people were dying of AIDS but nobody was paying attention,” she recalled. At that time the government had declared that there was no AIDS in the country.

Sister Martha knew better. She went to the families of the dying, but many were reluctant to accept her help. “They were all Buddhists and I was wearing the typical cloth of a nun. They did not want their neighbors to think that they had converted to Christianity.”

Sister Martha asked her order if she could dress like a civilian, but her superior said no. Impossible. But Sister Martha is not the type that takes no for an answer.

She wrote a long letter to the pope in Rome and after a while she got a reply: Under these particular circumstances she was allowed to change her dress.

She started her organization together with a Buddhist nun to make clear that it was not about religion or a particular faith. It was about humans helping humans in need. Through her hard work and persistence she was able to raise enough money to build three houses for the kids. She provides them and more than 50 adults in the village with life-saving medicine, paid for by international donors. “In all these years we haven’t lost one child,” she says proudly.

She started her organization together with a Buddhist nun to make clear that it was not about religion or a particular faith. It was about humans helping humans in need. Through her hard work and persistence she was able to raise enough money to build three houses for the kids. She provides them and more than 50 adults in the village with life-saving medicine, paid for by international donors. “In all these years we haven’t lost one child,” she says proudly.

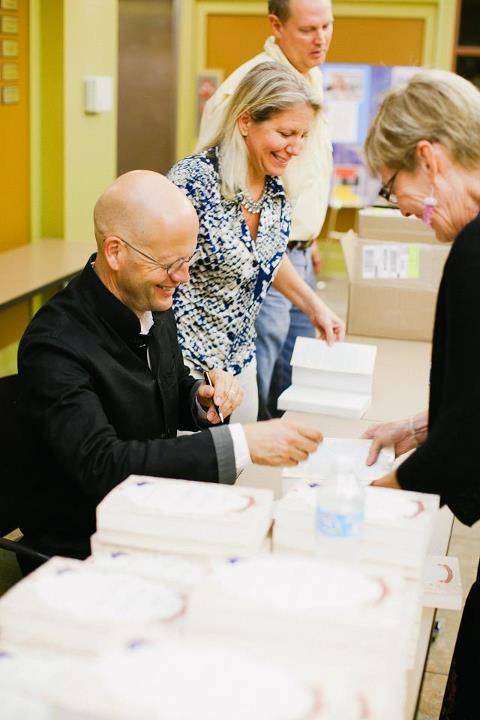

Once I returned to Germany, I started a fundraising drive for a new orphanage further south. Since then, we have raised more than $25,000 for Sister Martha’s efforts. And the donations keep coming in.

***

Mystic, CT

Mystic, CT

Transporting goods or traveling in Burma is never easy.

Transporting goods or traveling in Burma is never easy.